The Need for Social Disobedience

When I was 13, I learned there are things you don’t say at dinner parties.

My parents had invited over their long-time family friends, and when one of them casually asked me something Christianity related, I brushed it off by saying “oh no, I’m very atheist.”

To me, it was a meaningless statement. But to this White Anglo-Saxon Protestant L.L.Bean-catalogue family, it was abhorrent. I was oblivious to their reaction, but my parents later told me how visibly uncomfortable it made them and that I should avoid discussing the three “forbidden topics” at dinner parties:

- Politics

- Sex

- Religion

Now, I’m not so sure. Polite conversation may be doing more harm than good.

Civil Disobedience

Thoreau published Civil Disobedience in 1849 as a call to arms to deliberately violate and protest laws we believe unjust. He was incensed by slavery and the Mexican-American war, and to his credit, spent a short time in jail for refusing to pay taxes to a government he didn’t agree with.

Thoreau argued that we each have a conscience and that we should treat our conscience and sense of “what’s right” as a higher authority than the law:

“Why has every man a conscience, then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right.”

If we follow laws we think are wrong, he says, then we are enabling greater injustices to be carried out:

“Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice.”

What can we do about it? We can obey like sheep (bad), we can obey while trying to change the laws (less bad), or we can disobey them (good).

“Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?”

And this is Thoreau’s prescription: break the bad laws to influence government to change them, and to clear your conscience of supporting governmental wrongdoing:

“Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

Civil Disobedience is effective because it creates a lose-lose situation for whatever Power the Disobedience is directed towards.

If the Disobedience is ignored, then the Power is admitting defeat and allowing for further disobedience.

But if the Disobedience is punished, it must ultimately be punished by a demonstration of force, typically one that far exceeds the intensity of the Disobedience, and rallies supporters around the victim of the punishment (think Rosa Parks, Gandhi).

Civil disobedience provides a check against totalitarianism by showing that citizens won’t follow unjust laws and that there are limits to the use of discipline. Every power ultimately has some use of force as its last resort for enforcing compliance, and by exposing the absurdity of applying that force to reasonable behavior, citizens can keep government (or other) power in check.

Without the threat of civil disobedience, it would be easy for a government to progressively increase its power and control until we all end up in an Orwellian nightmare. I’m not saying that would happen, but it certainly could. And it might be happening somewhere else.

Ideological Totalitarianism

My extended family is going through some Facebook drama.

Apparently, one of my relatives (relative A) unfriended another relative (relative B) not because B was saying things that A disagreed with, but because B’s friends were saying things A disagreed with and A needed to deploy an emergency Safe Space.

There is hardly a better example of how extreme and counterproductive our intolerance for other viewpoints has gotten. Instead of ignoring the comments of these anonymous internet users, A had to sever their digital friendship with an in-law.

We’ve all encountered less extreme examples, and they’re easy to spot if you look for them. Someone shares a view that challenges the dominant ideology of whatever group they’re in, and everyone either gets really quiet, angry, or oh hey isn’t the weather being really weird right now?

While these reactions masquerade as being in the interest of social cohesion, they’re making us progressively more intolerant. Dismissing opinions from outside the in-group as ridiculous heresies further cements the group identity and increases our hyper-reactive mental immune response against any ideas that challenge the group narrative.

Every time you laugh with your friends about “how stupid Trump voters are,” you do a few things:

- You further cement the idea in your head that Trump voter = stupid.

- You create greater social consequences for those around you voicing anything pro-Trump, thus encouraging greater homogenization of your social group.

- You reduce your ability to reasonably engage with ideas that don’t fit your group’s narrative.

The more we punish diversity of thought, the more we lose perspective on how much diversity of thought there is, and the more intolerant we become against anyone who doesn’t check all our boxes for “right beliefs.”

And in the process, we end up weakening our minds and the minds of those around us.

Intellectual Fragility

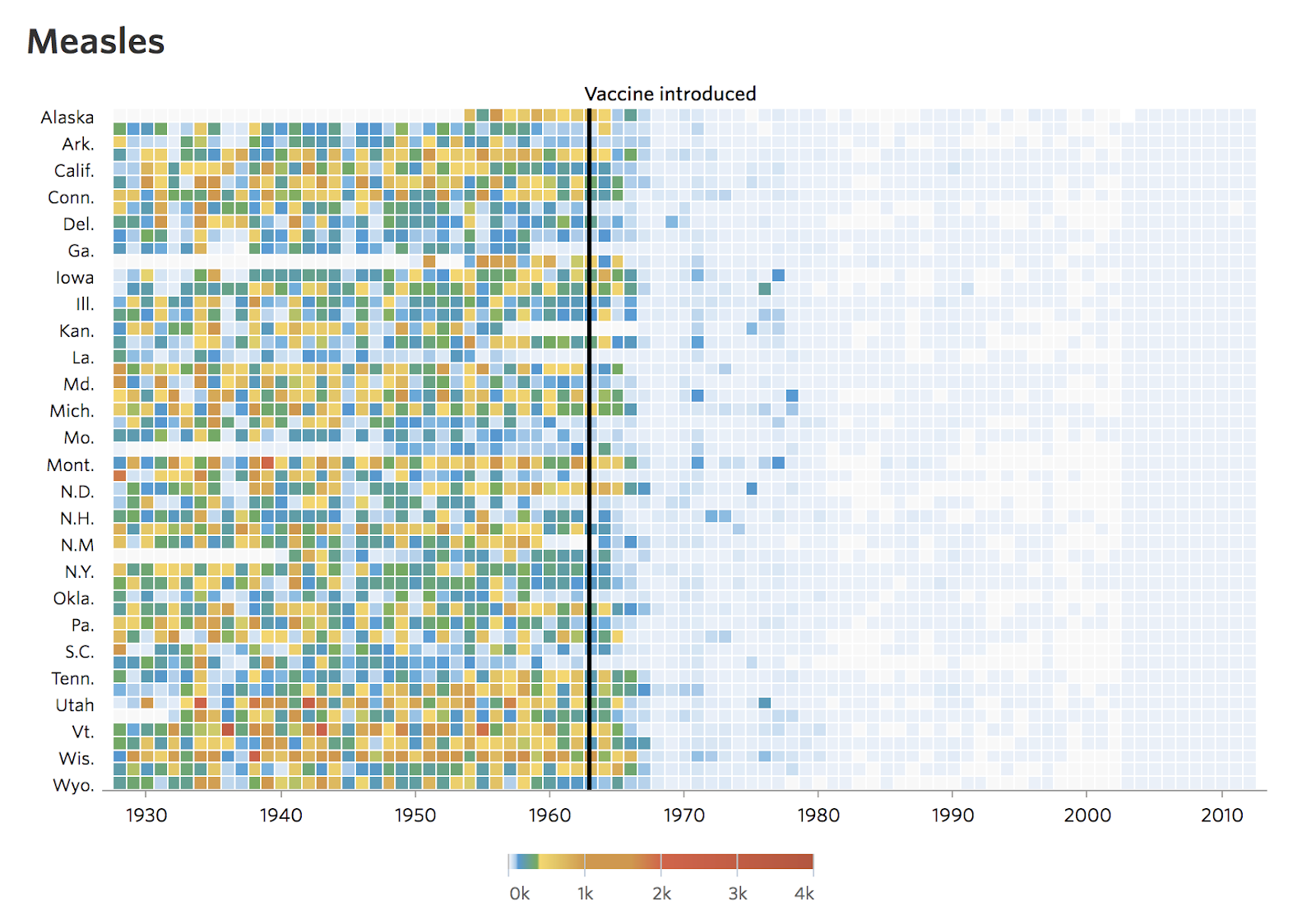

Despite the beliefs of a small minority, vaccines are good. Here’s an extremely impressive chart on Measles infections for example (from WSJ):

Vaccines prevent terrible diseases from developing later on in life by giving you a small dose of the infection early, so you can build up immunity to it. They’re the classic example of hormesis, a process where our bodies react positively to a small dose of something they’d react badly to a higher dose of.

Other examples similar to hormesis (or what Nassim Taleb calls “Antifragility”) aren’t hard to come by: fasting, exercise, market corrections, forest fires, romantic disagreements, heat exposure, all demonstrate hormesis. A little is good and makes the system stronger, a lot is bad and might lead to death, breakups, or Napa Valley turning into The Sahara of the West.

Too much isn’t the only problem though: a lack of exposure also makes the system weaker. Avoiding fasting, exercising, recessions, forest fires, disagreements, sweating, all really bad. When you don’t stress the system, it gets weaker and less able to handle the stresses when they inevitably pop up.

By allowing our ideologies to become sacrosanct, we’ve fragilized our minds. Not allowing our memes (societal ideas, not the silly cat pictures) to be challenged has made us intolerant of any ideas we disagree with. So intolerant that we have to purge our family members on social media.

We each have an obligation to try to respond positively to other people who have different ideas from us, but we also have a responsibility to un-fragilize the minds of others. To break the dinner party rule and try to find something you disagree with people on.

To “Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine.”

Social Disobedience

Civil disobedience challenges the totalitarian leanings of government, but what we need now is social disobedience to challenge the totalitarian leanings of ideology.

To socially disobey is to ignore the consequences of showing you have opinions that may be taboo to the group you’re in and share them anyway. To challenge the ideas of whatever person you’re talking to and try to have a productive discussion.

It doesn’t mean being an asshole, or belligerent, or difficult for the sake of being difficult. Rather, if someone asserts an idea that you don’t agree with, don’t shy away from voicing your disagreement. Try to understand where they’re coming from and talk about it.

You can’t just have different ideas, though, you have to be able to explain them really well. Well enough to make other people you talk to question their own beliefs.

The problem with many bad, infectious ideas is that no one challenges them, which makes you think you’re the only one who disagrees with whatever view is being expressed. It’s a mix of the Bystander Effect and the Emperor’s New Clothes phenomenon: when you’re sitting there thinking “this doesn’t sound right but I’m not going to say anything,” everyone else might be thinking the same thing but not saying it. The more that happens, the more you get in your head that you should adopt the most vocal opinions so you can fit in, and pretty soon you’re hanging out on Gab.

And this is where disagreeing with people in public can start to benefit you:it will make you extremely rigorous about how you form your own opinions.

When you’re agreeing with the in-group, you don’t need a reason for your beliefs. Rich Wall Street bankers are bad because duh. Let’s go get brunch. But when you show up to your Yale Foucault lecture and try to argue that differences between people don’t necessitate a destructive dominance hierarchy, you better come prepared.

The downside of all this? You’ll almost certainly offend someone. If you have the kind of job where you get told how to dress, you might get fired. But for every person so intolerant of conflicting views that they’ll block you on Facebook, there are at least two or three others who will think “finally someone said something.”

It just takes a little social disobedience.